Imagine, if you will, a perfect summer afternoon: slight breeze, cotton candy clouds lazily changing shape, fresh cut grass, laughter, loved ones. Can you put your finger on the scent laced through the air? It’s probably barbecue: that alchemy of fire and meat, so ubiquitous when thoughts turn to carefree, outdoor celebrating. There is no other food so closely related to a sunny vibe, and yet, in America, its historical roots are inevitably much more fraught.

It seems a no-brainer—to cook meat with fire—and Homo erectus began doing so about 1.8 million years ago.[1] As such, it goes without saying that ancient examples of this style of cooking is found the world over. The roots of modern Korean barbecue trace back during the Goguryeo era (37 B.C – 668 A.D)[2] through a line of nomadic ancestors, the Maek, who travelled with meat pre-salted which would help preserve it in their travels: “It is said the Maek group brought a hardy meat dish with them so they could have enough sustenance to survive the harsh elements that they expected to face on their journey.”[3] Maekjeok were “skewers roasted over a fire,”[4] which later became what is now the popular bulgogi, which means literally, “fire meat.”[5] In Korea the rise of Buddhism saw meat-eating generally banned and so banchan—small vegetable side dishes—took center stage. But later, with the Mogol invasion (1231-1259) meat dishes were brought back into the culture.[6]

Now Korean barbecue, popular across the diaspora, is a collective, social dining experience where meat is grilled at the table, served with banchan and beer. It seems easy to trace this path of fire meat over the Korean peninsula (and beyond) over thousands of years in five longish sentences, but what is really between the lines is the human history of invasions, war, cultural upheavals, adaptations, and reclamations directly influencing the food that people eat.

If we turn to America, barbecue as a cultural phenomenon is deeply embedded in certain regional identities: “barbecue as it exists in the United States, and especially in the South, is uniquely American. The word itself describes something beyond, and more profound, than a simple cooking technique or a type of restaurant. Barbecue means different things in different regions, finding disparate geographic expression.”[7] Four distinct traditions have evolved across the “barbecue belt”—Carolina, Texas, Memphis, and Kansas City barbecue. Arguments rage over the authenticity of each as sauces, styles, smoke, and types of meat differ across regions. Let’s not fail to mention the stark differences an aficionado sees between low and slow cooking over indirect flame versus grilling over high direct heat, where the former is the very definition barbecue and the latter is definitely not.[8]

And here is where the myth of America stands to address the crowd.

There is no food more all-American than barbecue, but rather what comes to mind in the popular imagination of someone who is not American is grilled hamburgers and hotdogs, steaks, and maybe sausages getting those perfect charred grill marks under the summer sun (refer back to that scent wafting through my introduction).

In the 1950s during the Cold War food was used as a national marker to distinguish the American “us” versus the Communist “them.” Barbecue became the representation of an American ethos because it had been a staple of frontier life and the frontier was synonymous with rugged individualism, exceptionalism, and freedom. To this day, these values are written into the DNA of how America sees—and markets—itself.[9] Barbecue was then “enthusiastically adopted by the urban middle class [and] it gradually acquired an association with home ownership and consumerism”[10] and suburban life. As Alexander Lee writes in “The History of the Barbecue,” after winning independence from the British, the westward expansion for territory saw these former colonists wage a brutal program against the Indigenous people which amounted to nothing less than genocide: “Yet perversely, it was in perpetrating these horrors that American settlers gained a fuller understanding, not only of native society, but also of barbecuing, which, as the Irish trader James Adair noted, was a specialty of the Chickasaw.”[11] Smoking meat was a necessity in the harsh conditions—as with the nomadic Maek people traversing what would become the Korean peninsula—in that tougher meats could be tenderized and the whole animal would be used. Lee goes on to say: “by the time of the Texas annexation (1845), the smell of barbecued meat (usually beef) had become as familiar a feature of pioneer towns as tumbleweed and dust.”[12]

But the brutality of the frontier was just one leg of barbecue’s journey; to get the whole story we have to go back even further to the 15th century, into the Spanish colonization of the Caribbean, specifically the encounter with the Taino people on Hispaniola (The Dominican Republic and Haiti).

There seems to be some uncertainty over the origins of the term barbecue, but many sources see it drawn from the Taino word barbacoa. Barbacoa was a “sacred fire pit.”[13]

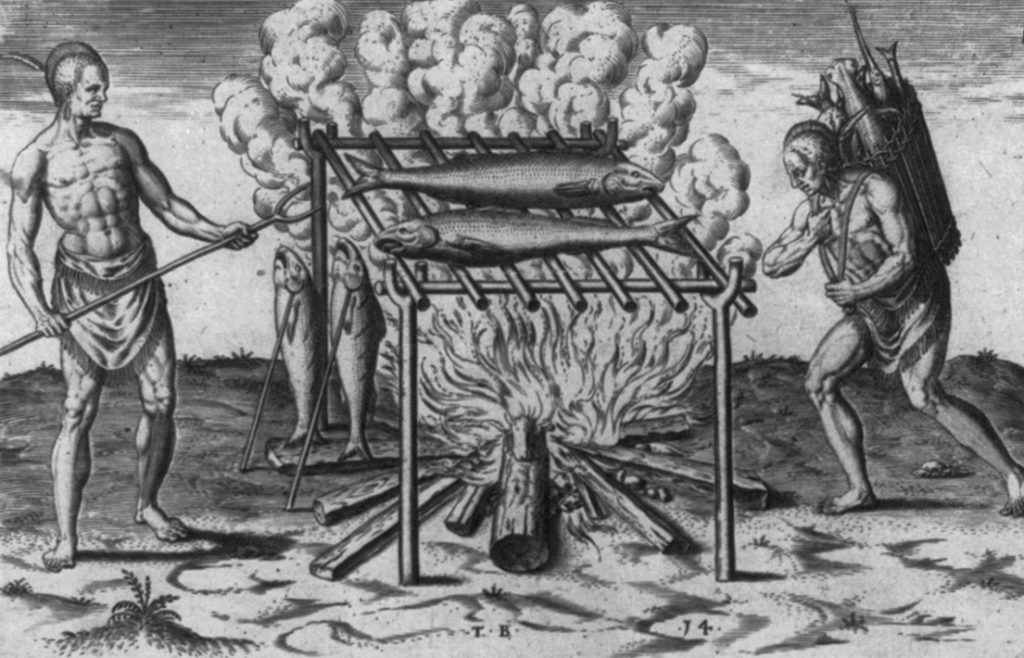

Or else it was the raised wooden platform that was used for a variety of purposes, or it was a type of raised bed, or a type of raft, or eventually it was understood to be a style of cooking meat over an open fire on a raised wooden lattice, and then by the time the word had made it over to America, American colonists “[did] not appear to have recognised it as a ‘native’ term, or even as a word used to describe a method of cooking. Instead, they saw it as something like a picnic: that is, as a social gathering, usually held outdoors, at which animals were roasted whole.”[14] The only reason I stress this potential for misunderstanding is because the Taino themselves did not have a written language: “so much of their legacy is based on written accounts by outsiders, the artifacts they left behind, and the vocabulary and customs that have survived to this day.”[15] Barbacoa may not have been the precise Taino word, but rather the Spanish interpretation of a language they had never heard before: “Other European explorers reported home that natives in northern South America, especially Guiana [now Guyana], may have called their version of the barbacoa a babracot or babricot or barboka. These are possible dialects of the many tribal languages or further clumsy attempts to mimic the native words.”[16] In these gaps of language where misunderstandings bloom is where power dynamics often reveal themselves. In any case, “barbeques the way that Americans know them now meat cooked over a grill or pit, covered in spices and basting sauce originated in the Caribbean.”[17] Again is seems as though the method of cooking with smoke, on a raised platform was a necessity for people who hunted and lived on subsistence farming: “First and foremost, it meant that nothing was wasted. Since it made even the toughest meat tender, virtually every part of an animal could be eaten. It also required little fuel; and best of all, it made for a tasty meal.”[18] Colonizers came into contact with this way of cooking, and though they may have enjoyed it, there was still disdain for the native culture and practices which was largely deemed ‘barbaric,’ by these slave owners.

Initially the colonizers had no need to make use of this cooking technique since they had access to the best cuts of meat which didn’t require tenderizing and they had access to fuel.[19] This would change, though, in America when enslaved people were brought from the Caribbean and West Africa: “West and Central Africans had always had their own versions of the barbacoa and spit roasting of meat.While living in a tropical climate, salting, spicing and half-smoking meat upon butchering was key to ensuring game would make it back to the village with minimal spoilage.”[20]

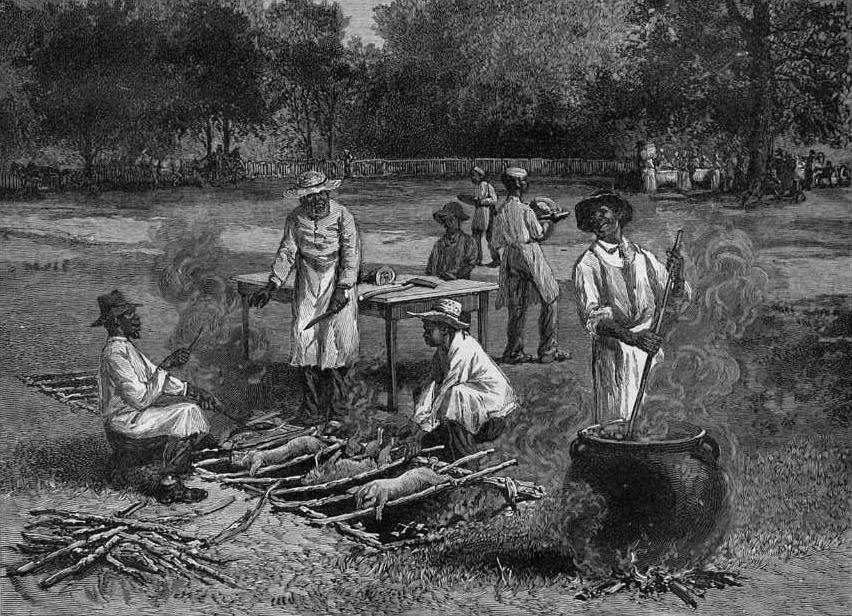

At some point too, the raised barbacoa was replaced with a pit dug into the ground—also an Indigenous style of cooking with a thousand year history, as in the Hawaiian kālua—and the labour intensive work of the pit was carried out by the pit master, a slave:

Someone had to clear the area where the barbecue was held, chop and burn the wood for cooking, dig the pit, butcher, process, cook and season the animals, serve the food, entertain the guests and clean up afterward. Given the racial dynamics of the antebellum South, enslaved African Americans were forced to do that work.[21]

The slaves themselves were given only the undesirable and unwanted portions, but nonetheless were able to create something valuable out of nothing: “Slaves became adept at taking marginal cuts of meat such as ribs and preparing them in such a way that they were quite tender and delicious, which as time went by became staples of modern BBQ preparation, and ironically for many, the preferred cuts of meat for BBQ.”[22]

Barbecues had became a popular social and political function in the second half of the 18th century, with colonial elites doing the hosting, “In 1769, George Washington, for example, noted in his diary that he had gone ‘up to Alexandria for a Barbecue and stayed all Night’. Four years later, he held one of his own at Accatinck.”[23] Because of the length of time it took to prepare the meat, beginning at dawn and not served until early evening, barbecues as a social occasion were eventually mined for political privilege: “Candidates for public office saw the relatively large assemblies of potential voters and the relaxed atmosphere as a fine opportunity to deliver campaign speeches. So it wasn’t long before political barbecues came into being – barbecues organized and paid for by candidates.”[24] As such it reads as though barbecue—the cooking technique and the communal event—unwittingly became the perfect storm where race, class, and politics collided when it was appropriated and extracted from its original contexts. And really this is nowhere near scratching the surface of the deep barbecue culture of the men and women who worked the pits and the legacy they have left their descendants. Complexity gives us dimension, in flavour, and in understanding. So perhaps our various cultural phenomenon—practices that evolved alongside untold violence and displacement—also necessarily holds space for celebration, adaptation, and liberation.

by Nadia Ragbar

[1] https://www.livescience.com/32724-whats-the-history-of-the-barbecue.html

[2] https://nextshark.com/korean-bbq-history/#:~:text=Ancient%20history%3A%20Molded%20by%20eras,who%20lived%20in%20that%20era.

[3] https://asianinspirations.com.au/food-knowledge/korean-barbecue-a-delicious-history/

[4] https://nextshark.com/korean-bbq-history/#:~:text=Ancient%20history%3A%20Molded%20by%20eras,who%20lived%20in%20that%20era.

[5] https://mykoreankitchen.com/bulgogi-korean-bbq-beef/

[6] https://nextshark.com/korean-bbq-history/#:~:text=Ancient%20history%3A%20Molded%20by%20eras,who%20lived%20in%20that%20era.

[7] https://www.eater.com/2016/6/16/11889444/where-to-eat-barbecue-styles

[8] https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-evolution-of-american-barbecue-13770775/

[9] https://www.historytoday.com/archive/historians-cookbook/history-barbecue

[10] ibid

[11] ibid

[12] ibid

[13] https://blackthen.com/the-connection-between-african-americans-and-the-history-of-barbeque/

[14] https://www.historytoday.com/archive/historians-cookbook/history-barbecue

[15] https://larisanjou.com/2020/07/19/boricua-barbacoa-the-journey-to-self/

[16] https://amazingribs.com/barbecue-history-and-culture/barbecue-history/

[17] https://www.livescience.com/32724-whats-the-history-of-the-barbecue.html

[18] https://www.historytoday.com/archive/historians-cookbook/history-barbecue

[19] ibid

[20] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jul/04/barbecue-american-tradition-enslaved-africans-native-americans

[21] https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/08/13/media-has-erased-long-history-black-barbecue-skewing-our-understanding/

[22] https://www.republic-online.com/news/osawatomie/bbq-roots-are-connected-to-slavery/article_113b15e2-f1d4-11e9-8631-c353b4b1f564.html#:~:text=While%20the%20culinary%20art%20of,in%20the%20colonial%20era%20of

[23] https://www.historytoday.com/archive/historians-cookbook/history-barbecue

[24] https://www.haaretz.com/.premium-the-politics-of-the-barbecue-1.5333246?v=1651035253691S