By the end of summer that bright lemony sunshine tempers into something more languid and gives over to a sepia-toned atmosphere; we become nostalgic for a summer that isn’t even over, but is each day maturing into autumn. Our tastes may turn to the warming spices—ginger, cloves, black pepper, turmeric, cardamom, cayenne, and cinnamon.

Of these, cinnamon’s distinct fragrance instantly conjures memories of the foods that both comfort and delight us: bowls of oatmeal, apple crisps, decadent cinnamon rolls, and even jewel-toned rice pilafs. Where cumin was able to travel the globe creating new flavour profiles as it crossed borders (think about the difference between Indian cuisine and Mexican, which both rely on cumin to different effect), cinnamon stays true only to itself, unmistakeable in its warmth and fragrance.

Cinnamon is the dried inner bark from evergreen trees of the laurel family,[1] and is typically divided into two categories: “verum (‘true’) and cassia,” the former found primarily in Sri Lanka, and the later a less-expensive cinnamon cultivated in China.[2] As with so many spices, its place in early history was exalted, “considered so valuable during this time it was equal in worth to gold and ivory. [Cinnamon] was regarded as a suitable gift for Monarchs and for Gods,”[3] and one ancient Greek inscription depicts cinnamon being gifted to Apollo.[4]

Another myth sees the phoenix, the symbol of rebirth, building its nest from cinnamon and cassia sticks.[5] In ancient Egypt cinnamon, alongside cumin, was used in embalming practices and rituals where the use of “botanicals including herbs, spices, resins, gums, and oils, was thought to increase the likelihood of resurrection.”[6] Additionally, “Cinnamon oil was another ingredient essential to the ancient Egyptians for its antifungal, antiviral, bactericidal and larvicidal properties.”

In a tragic and paltry turn, “Roman Emperor Nero ordered a year’s supply of cinnamon be burnt after he murdered his wife”[7] as a show of remorse. I mention this because of the ancient world through-line pairing rebirth and resurrection with cinnamon—perhaps Emperor Nero chose cinnamon for its economic value but also for this symbolic gesture. Later, during the Middle Ages physicians would use cinnamon medicinally “to help treat cold and throat ailments such as coughing, hoarseness and sore throats.”[8]

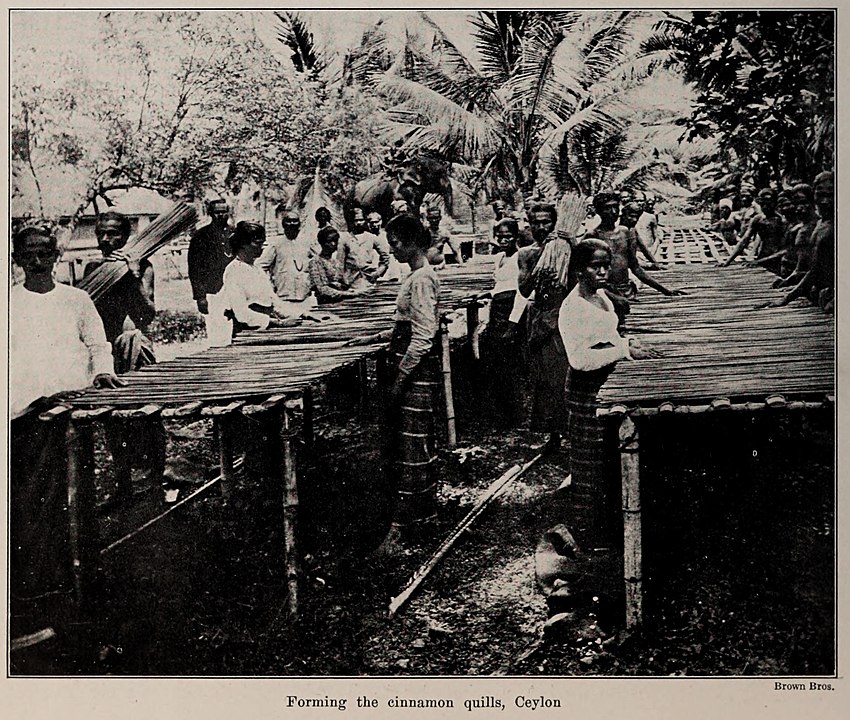

Cinnamon was an extremely valuable commodity to early Arab traders: “[b]ecause cinnamon was transported via land routes that were difficult to traverse, it was very expensive. Its high cost made it into a status symbol in Europe.”[9] However, one practical reason that made cinnamon so valuable was its preservative quality—it was able to preserve meat by inhibiting “the bacteria responsible for spoilage, with the added bonus being the strong cinnamon aroma masked the stench of aged meats.”[10] And in this way cinnamon became yet another impetus, or excuse, for colonization: “the rise in demand resulted in European explorers setting out to find cinnamon’s source. Both Christopher Columbus and Gonzalo Pizarro sought the spice in the New World. It was found in Ceylon [now Sri Lanka] by Portuguese explorers who conquered the island and enslaved its people. This gave them control of the cinnamon trade for a century.[11]

In the 17th century, the Dutch seized Ceylon from the Portuguese, “demanding outrageous quotas from the poor labo[u]ring Chalia caste,” and by 1795 “England seized Ceylon from the French, who had acquired it from their victory over Holland during the Revolutionary Wars.”[12] This monopoly would end beginning in 1833 when it was found that cinnamon could be grown easily in “such areas as Java, Sumatra, Borneo, Mauritius, Réunion, and Guyana.”[13]

Today ground cinnamon and cinnamon sticks are a common pantry staple, but it is easy to see why it was such a prized resource when we also consider its natural health benefits, in addition to the anti-fungal, anti-viral, and anti-bacterial properties recognized by the ancients. Cinnamon manages blood sugar; rebalances the bacteria to support digestive health; may provide short-term reduction of blood pressure; and may also help to maintain brain health.[14]

The beauty of cinnamon is the way its fragrance and flavour is both bold and sweet (embodied in Michael Ondaatje’s love poem “The Cinnamon Peeler”[15]).

Its smell is enticing and embracing taking us right back into memories of comforting foods and drinks, but also it doesn’t take much in a recipe to leave its mark, and can easily overtake and mask. The nurturing yin and the dominating yang held together in the bark of this evergreen.

[1] https://www.britannica.com/plant/cinnamon

[2] https://www.finedininglovers.com/article/spice-trail-history-cinnamon

[3] https://www.myspicer.com/history-of-cinnamon/

[4] https://www.finedininglovers.com/article/spice-trail-history-cinnamon

[5] ibid

[6] https://christineelder.com/spooky-embalming/#:~:text=Significant%20Native%20Plants%20Used%20for%20Embalming&text=Cinnamon%20oil%20was%20another%20ingredient,and

[7] https://www.thespruceeats.com/history-of-cinnamon-1807584#:~:text=Cinnamon%20Origin%20and%20History,amomon%2C%20meaning%20fragrant%20spice%20plant.

[8] https://www.myspicer.com/history-of-cinnamon/

[9] https://www.spiceography.com/cinnamon/

[10] https://www.thespruceeats.com/history-of-cinnamon-1807584#:~:text=Cinnamon%20Origin%20and%20History,amomon%2C%20meaning%20fragrant%20spice%20plant.

[11] https://www.spiceography.com/cinnamon/

[12] https://www.thespruceeats.com/history-of-cinnamon-1807584#:~:text=Cinnamon%20Origin%20and%20History,amomon%2C%20meaning%20fragrant%20spice%20plant.

[13] ibid

[14] https://www.bbcgoodfood.com/howto/guide/health-benefits-cinnamon

[15] https://www.lyrikline.org/en/poems/cinnamon-peeler-6570

by Nadia Ragbar